Treating Severe Chronic Periodontitis

Nonsurgical periodontal therapy and intracoronal splinting can stabilize teeth with questionable to hopeless prognoses for many years

Dwight McLeod, DDS, MS | Hesham Abdulkarim, BDS, MSD Grishonda Branch-Mays, DDS, MS | David Scott Dunivan, DMD, MS Romana Muller, RDH, MSDH, EdD

Chronic periodontitis is a multifactorial disease with bacterial etiology that is exacerbated by host response. Untreated severe chronic periodontitis often presents with a myriad of clinical and radiographic findings, including gingival inflammation, severe clinical attachment loss, purulent exudate, mobile teeth, pathologic tooth migration, severe alveolar bone loss, and furcation defects.1,2 A thorough understanding of the underlying causes of clinical changes in untreated severe chronic periodontitis can improve management of the condition and lead to better treatment outcomes. The elimination of etiologic factors is essential to disease control and periodontal stability.3

Teeth affected by severe periodontitis and Class II/III mobility are often deemed questionable or hopeless and recommended for extraction but rarely considered for therapy and reassessment.4 Greater knowledge and understanding of periodontitis should warrant the most appropriate time to devise a comprehensive treatment plan for patients. According to the results of retrospective studies on tooth loss, teeth with questionable to hopeless prognoses can be maintained for many years and prognostication is not reliable in determining treatment outcomes.5 Effective nonsurgical periodontal therapy and thorough management of etiologic and risk factors can positively impact clinical parameters associated with prognosis.3 This includes the management of occlusal factors to help stabilize teeth with severe chronic periodontitis and secondary occlusal traumatism. Therefore, unless tooth loss is imminent, the timing of extraction should be considered with preference toward after, as opposed to before, initial therapy.

The following case report involves a patient with severe chronic periodontitis who was initially treatment planned for full-mouth extractions and complete dentures but was ultimately treated and stabilized with nonsurgical periodontal therapy, limited orthodontic treatment, intracoronal splinting, and supportive periodontal therapy over a 4-year period.

Case Report

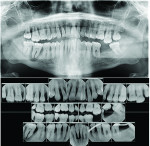

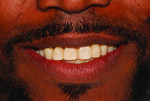

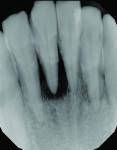

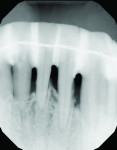

A 37-year-old African American male patient without significant medical history presented for dental treatment with the chief complaint that he would like to have his teeth fixed. He reported he was a nonsmoker and consumed one alcoholic beverage per day. Previously, the patient was seen by a general dentist who recommended full-mouth extractions and complete denture rehabilitation, but he was referred from a community center by another general dentist for a last-minute periodontal consultation. The initial preoperative clinical and radiographic examinations (Figure 1 through Figure 6) revealed severe chronic periodontitis, which was classified as Stage 4 Grade C. Given the patient's age, the preservation of natural detention and of maximal masticatory function were considered essential. Therefore, the case was treatment planned for phase I periodontal therapy, limited orthodontics, intracoronal splinting, interproximal bonding, and phase III periodontal therapy. The patient accepted the treatment plan, and verbal and written informed consent were obtained.

Case Management

The causes and risk factors of periodontal disease were explained, and oral hygiene instructions were given. Phase I periodontal therapy under local anesthesia was accomplished over two visits, along with the extractions of the remaining maxillary and mandibular second and third molars (Figure 7 through Figure 9). Due to the patient's conflicting work schedule and the need for intense patient education with verification of plaque-control compliance, periodontal reevaluation was completed after three successive periodontal maintenance visits. Any residual subgingival calculus was removed during the first and subsequent supportive periodontal therapy visits. After the patient's periodontal condition was improved, limited orthodontic therapy was completed in the maxillary arch to realign tooth No. 7 (Figure 10 through Figure 12) and intracoronal splinting and interproximal bonding, utilizing orthodontic braided wire and composite material, was rendered in both full arches with rebonding in the area of teeth Nos. 8 and 9 (Figure 13 through Figure 17).

Clinical Outcomes

The patient's periodontal disease improved and was maintained with supportive periodontal therapy. Limited orthodontic therapy contributed to the realignment of his teeth and improved his esthetics, while intracoronal splinting and comprehensive occlusal adjustment resulted in stability of both arches. During the 4 years following treatment, some rebounding occurred in the patient's periodontal probing depths, but this did not warrant additional periodontal therapy. After

4 years of supportive periodontal therapy and constant reinforcement of patient education on plaque control, the patient remained functionally dentate with a stable periodontium (Figure 18 through Figure 24).

Discussion

Periodontal disease is multifactorial, involving primary and secondary contributing factors. Although chronic periodontitis is the most widespread form of the disease, elimination of etiologic and contributing factors can lead to disease stability and an improved periodontal prognosis.6 Nonsurgical periodontal therapy, which is considered the first-line treatment for periodontal disease, is the most affordable way to pursue periodontal care and reduce systemic inflammation associated with untreated periodontitis. In addition, achieving occlusal harmony is essential in treating severe chronic periodontitis.7 Occlusal stability can be accomplished through the resolution of severe gingival inflammation, limited or comprehensive occlusal adjustment and/or orthodontic therapy, and intracoronal or extracoronal splinting.5,8,9 Furthermore, the use of composite resins to stabilize teeth through the bonding of interproximal spaces can also improve dental esthetics, resulting in the reduction of black triangles and improving the shape of teeth.

In this case, access to periodontal therapy resulted in control of the patient's periodontal disease, eliminating the need for full-mouth extractions and complete dentures. Moreover, a mutually protected and stable occlusion was established. A comparison of the preoperative and 4-year follow-up periapical radiographs of the patient's mandibular incisors reveals that the treatment resulted in improvement in the crestal bone quality and density (Figure 25 and Figure 26).

The natural dentition has the ability to improve drastically when the intraoral conditions are harmonious. No restorations can truly replace the natural dentition. When treatment planning patients with severe chronic periodontitis, significant consideration should be given to retaining teeth by conducting the initial phase of periodontal therapy. Patients who do not present with other dental comorbidities, such as caries or endodontic pathoses, should be given every opportunity to be treated with nonsurgical periodontal therapy and periodontal maintenance. Pre- and posttreatment prognoses must be assessed and short- and long-term treatment options must be considered before a final decision to extract teeth is made by the clinician. If the elimination of etiologic and risk factors is accompanied by patient compliance with plaque control, nonsurgical periodontal therapy can lead to desirable outcomes for patients with severe chronic periodontal disease and result in better prognoses and retention of teeth.3,10

Conclusion

When the underlying causes of untreated severe chronic periodontitis are addressed and managed, improved treatment outcomes can be achieved. This case report highlights the effective use of nonsurgical periodontal therapy, orthodontic and occlusal therapy, and intracoronal splinting to achieve periodontal stability and retain a patient's teeth. It demonstrates that teeth that are initially assigned a hopeless prognosis can be saved if healing is supported by suitable physiologic oral conditions. In that regard, it also reveals how clinicians can be ineffective at prognosticating and the importance of not allowing prognosticating to impact decisions related to the timing of extractions, especially if a patient presents with severe chronic periodontitis without other dental comorbidities.

About the Authors

Dwight McLeod, DDS, MS

Professor

Dean

Missouri School of Dentistry & Oral Health

A.T. Still University

St. Louis, Missouri

Hesham Abdulkarim, BDS, MSD

Associate Professor

Specialty Comprehensive Unit Director

Advanced Periodontal and

Dental Implant Care

Missouri School of Dentistry & Oral Health

A.T. Still University

St. Louis, Missouri

Grishonda Branch-Mays, DDS, MS

Professor

Senior Associate Dean of Academic Affairs

Missouri School of Dentistry & Oral Health

A.T. Still University

Kirksville, Missouri

David Scott Dunivan, DMD, MS

Assistant Professor

Specialty Comprehensive Unit Director

Periodontics

Missouri School of Dentistry & Oral Health

A.T. Still University

St. Louis, Missouri

Romana Muller, RDH, MSDH, EdD

Associate Professor

Missouri School of Dentistry & Oral Health

A.T. Still University

St. Louis, Missouri

References

1. Harris RJ. Untreated periodontal disease: a follow-up on 30 cases. J Periodontol. 2003;74(5):672-678.

2. Papapanou PN, Sanz M, Buduneli N, et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S173-S182.

3. Nieri M, Muzzi L, Cattabriga M, et al. The prognostic value of several periodontal factors measured as radiographic bone level variation: a 10-year retrospective multilevel analysis of treated and maintained periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 2002;73(12):1485-1493.

4. Moreira C, Zanatta F, Antoniazzi R, et al. Criteria adopted by dentists to indicate the extraction of periodontally involved teeth. J Appl Oral Sci. 2007;15(5):437-441.

5. Graetz C, Ostermann F, Woeste S, et al. Long- term survival and maintenance efforts of splinted teeth in periodontitis patients. J Dent. 2019;80:49-54.

6. Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, Van Dyke TE, et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S74-S84.

7. Serio FG. Clinical rationale for tooth stabilization and splinting. Dent Clin North Am.1999;43(1):1-6.

8. Kathariya R, Devanoorkar A, Golani R, Bansal N, Vallakatla V, Saleem Bhat MY, et al. To splint or not to splint: the current status of periodontal splinting. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2016;18(2):45-56.

9. Jochebed SR, Ganapathy D. Effect of splinting on periodontal health - A review. Drug Invent Today.2020;14(5):665-668.

10. Graetz C, Dörfer CE, Kahl M, et al. Retention of questionable and hopeless teeth in compliant patients treated for aggressive periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(8):707-714.