Effectiveness of Oral Rinse as an Adjunct to Toothbrushing: A 6-Week Clinical Trial Management of Plaque and Gingivitis With Daily Oral Rinsing

Jeffery L. Milleman, DDS, MPA; Reinhard Schuller, MSc; and Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS, MAGD

ABSTRACT

A common condition found in many patients, gingival inflammation results from irritation from dental plaque and the bacteria contained in plaque. Although effective management of dental plaque and the resulting gingivitis through daily homecare continues to be heavily emphasized, the high prevalence of oral diseases globally suggests that most individuals do not achieve sufficient plaque removal with their manual toothbrushing routine. To help enhance a patient's homecare regimen, daily oral rinsing has been shown to improve oral hygiene. The simple use of mouthwash after toothbrushing optimizes plaque removal while leading to an improvement in gingival health. This article reviews a single-center, randomized, controlled, single-blind, 6-week study designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a professional chlorhexidine alternative oral care mouthrinse as an adjunct to toothbrushing with sodium fluoride toothpaste with regard to plaque removal and gingivitis reduction.

Gingival inflammation is a common occurrence and is associated with dysbiotic biofilm accumulation.1 Effective management of dysbiotic biofilm and gingivitis through daily homecare continues to be a high priority. Dental professionals recommend brushing at least twice daily and daily interdental cleaning to remove plaque and reduce the risk of tooth decay and gum disease.2 A recent study by Ebel and coworkers assessed the impact of brushing time and oral care techniques in a young adult population (18 years old) with regard to plaque removal efficiency with a standard manual toothbrush.3 They reported that participants distributed their brushing time across surfaces unevenly, which explained the observed variance of plaque removal and areas of bleeding. The specific brushing technique employed in their study (eg, modified Bass, Stillman, scrub bush) was determined to be of minor importance, and the authors concluded that their results indicated that systematic interventions or prophylactic programs should emphasize the importance of brushing all surfaces and not neglecting any teeth. The high prevalence of oral diseases globally,4 however, suggests that most individuals do not achieve sufficient plaque removal with their manual toothbrushing routine alone. Although dental professionals stress the importance of improving brushing habits with patients, behavior modification is challenging.

The question for dental healthcare professionals, therefore, becomes, "How can patients improve their daily homecare?" Clinical studies have proven that improvement in oral hygiene can be achieved through the use of daily oral rinsing.3,5-8 The simple process of swishing mouthwash after toothbrushing can result in a reduction in plaque and gingival inflammation and improved gingival health, which has been shown to have a positive effect on systemic health.9

This article reviews a single-center, randomized, controlled, single-blind study designed to evaluate the safety and the efficacy of the use of OraCare Health Rinse (OraCare, oracareproducts.com) as an adjunct to toothbrushing with sodium fluoride toothpaste on plaque removal and gingivitis reduction. Additionally, treatment examples are presented in which oral rinsing was utilized to aid in the management of plaque and gingival issues.

Methods and Materials

The objective of this single-center, randomized, controlled, examiner-blind, 6-week clinical trial was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of OraCare Health Rinse as an adjunct to toothbrushing with a fluoride toothpaste compared to toothbrushing alone for the reduction of gingivitis and plaque when used unsupervised, twice daily at home. Participants were instructed to refrain from home oral hygiene for 8 to 12 hours before each examination visit and to not eat, drink, or smoke 30 minutes prior to the appointment. Analyses were performed at 2 weeks and 6 weeks for each efficacy variable, using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with treatment as a factor and the corresponding baseline value as a covariate. Post-ANCOVA pairwise comparisons between treatments were made using a two-sided Dunnett's test, which controls the error rate for the simultaneous comparisons. Also, all comparisons were two-sided with a 0.05 significance level.

Study Population:An initial group of 107 generally healthy male and female subjects were screened, 97 were randomized, and 91 completed the trial. To participate in this study, all subjects fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria:To be eligible for study participation, subjects met the following criteria: (1) a generally healthy male or female at least 18 years of age; (2) a self-reported twice-daily, regular manual toothbrush user; (3) willing to refrain from all oral hygiene 8 to 12 hours prior to each study visit, and discontinue eating, drinking, and smoking 30 minutes prior to each study visit; (4) have at least 18 natural teeth with scorable facial and lingual surfaces; teeth that were grossly carious, orthodontically banded, exhibiting general cervical abrasion and/or enamel abrasion, or third molars were not included in the tooth count; (5) have a gingival index score ≥1.95; (6) have a plaque index score ≥1.95 following an 8- to 12-hour plaque accumulation period; (7) have at least 20 bleeding sites based on the gingival bleeding index (GBI); (8) have an absence of advanced periodontitis based on a clinical examination with probing depths of 4 mm or less except for two sites allowed with probing depths of 5 mm; (9) willing and able to refrain from dental treatment during the course of the study, except on an emergency basis.

Exclusion Criteria: Subjects presenting with any of the following were not included in the study: (1) history of adverse effects, or oral soft- or hard-tissue sensitivity to any ingredient in the test materials; (2) use of a stannous fluoride toothpaste or any chemotherapeutic mouthwash in the past 30 days; (3) self-reported serious medical conditions; (4) self-reported as pregnant or nursing; (5) under treatment for a heart condition requiring the use of a pacemaker; (6) having any health condition that would place the subject at increased risk or preclude the subject's full compliance with or completion of the study; each subject reviewed the ingredients' list to ensure there were no drug allergy issues, and subjects were interviewed at each examination timepoint to see if there were any changes in medical history and to evaluate oral findings; (7) requiring antibiotic premedication prior to dental procedures; (8) having had antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-coagulant medication, or chemotherapeutic antiplaque/anti-gingivitis therapy within 30 days of the screening exams; (9) participation in any study involving oral care products, concurrently or within the 30 days of the screening examinations; (10) unwilling to discontinue use of other oral hygiene products for the duration of the study; (11) presence of severe periodontal disease or being actively treated for periodontal disease; (12) presence of grossly carious, fully crowned, or extensively restored teeth; (13) presence of orthodontic appliances, perioral piercings, or removable partial dentures; (14) presence of significant oral soft-tissue pathology based on a visual examination; (15) presence of heavy calculus deposits.

Following informed consent procedures and collection of baseline demographics, qualified participants received an oral examination and assessment for the modified gingival index (MGI), GBI, and Lobene-Soparkar modification of the Turesky modification of the Quigley-Hein plaque index (LSPI) per sequence (periodontal pocket depth [PPD] and bleeding on probing [BOP] at screening/baseline and 6 weeks only). This clinical oral examination included the following assessments (in order): oral safety, through soft- and hard-tissue examination for evidence of inflammation, irritation, or other abnormalities; gingivitis, according to the MGI10; gingival bleeding, according to the GBI described by Saxton and van der Ouderaa11; PPDs and BOP; and supragingival plaque levels, according to the LSPI.12,13

Participants who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and consented to participate in the study were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: (1) Control group: twice daily brushing with an American Dental Association (ADA) accepted manual soft toothbrush (Pro-Sys® 35-tuft, Benco Dental, pro-sys.com) and ADA accepted 0.243% sodium fluoride Crest® Cavity Protection dentifrice (Procter & Gamble, us.pg.com). (2) Test group: twice daily brushing with the same manual soft toothbrush and 0.243% sodium fluoride dentifrice used by the Control group, followed immediately by the use of OraCare Health Rinse. Subject in both groups brushed in their normal fashion and did not control their brushing time. Subjects in the Test group used the mouthrinse according to the manufacturer's instructions (three pumps, sit for 30 seconds, rinse for 60 seconds).

Subjects were provided verbal and written instructions on the use of their assigned product regimen. The first assigned use was performed at the clinical site under the supervision of study personnel. All subjects maintained a daily diary to document compliance with the use of their assigned products.

Following the screening/baseline examinations, subjects returned at 2 weeks and 6 weeks for the same assessments for oral safety, gingival health, and plaque. PPD and BOP were assessed at screening/baseline and 6 weeks only. Clinical efficacy assessments were performed by a single, trained, calibrated examiner at screening/baseline, week 2, and week 6.

During the study, subjects were instructed to refrain from using any oral care products other than the assigned products provided to them. This included avoiding the use of other toothbrushes, toothpaste, mouthwashes, chewing gum, breath film, mints, floss, interdental cleaning aids, or other oral care cleaning aids for the duration of the study. Subjects were also instructed to follow their usual dietary habits.

Gingival Inflammation

Gingival inflammation was assessed according to the MGI and scored in six areas (distobuccal, midbuccal, mesiobuccal, distolingual, midlingual, and mesiolingual) of all scorable teeth using a scale of 0 through 4 as described as follows: 0 = normal (absence of inflammation); 1 = mild inflammation (slight change in color, little change in texture) of any portion of the entire gingival unit; 2 = mild inflammation of the entire gingival unit; 3 = moderate inflammation (moderate glazing, redness, edema, and/or hypertrophy) of the gingival unit; 4 = severe inflammation (marked redness and edema/hypertrophy, spontaneous bleeding, or ulceration) of the gingival unit. Whole mouth MGI scores were calculated by summing all scores and dividing by the number of scorable sites examined.

Expanded Gingival Bleeding

Gingival bleeding tendency was assessed according to the expanded bleeding index (EBI). The gingiva was lightly air-dried, and a periodontal probe was inserted to a depth of approximately 1 mm. The probe was then moved gently around the tooth at an angle of approximately 60 degrees to the long axis of the tooth, stroking the inner surface of the sulcular epithelium. Each of the six aforementioned gingival areas of the scorable teeth was probed in a similar manner, and after waiting approximately 30 seconds, the number of gingival sites which bled were recorded, according to the following scale: 0 = absence of bleeding after 30 seconds; 1 = bleeding observed after 30 seconds; and 2 = immediate bleeding observed.

Plaque Index

Supragingival dental plaque was assessed by using a red solution, and each tooth was scored in the six areas, according to the following criteria: 0 = no plaque; 1 = separate flecks or discontinuous band of plaque at the gingival (cervical) margin; 2 = thin (up to 1 mm), continuous band of plaque at the gingival margin; 3 = band of plaque wider than 1 mm but less than one-third of the tooth surface area; 4 = plaque covering one-third or more but less than two-thirds of the tooth surface area; 5 = plaque covering two-thirds or more of the tooth surface area.

A whole mouth plaque index was calculated for each participant by adding all the individual scores and dividing this sum by the number of measurements. To understand the plaque removal efficacy of each toothbrush in hard-to-reach areas, separate subsets of the plaque index were calculated for the gingival margin and the interproximal surfaces. Gumline plaque index scores were calculated by summing the number of gingival margin (buccal and lingual) scores and dividing by the number of measurements. Interproximal plaque index scores (mesial and distal) were calculated by summing the number of interproximal site scores and dividing by the number of measurements.

Follow-up

Study-related adverse events were monitored to resolution by the investigator for at least 30 days following study completion or discontinuing use of the investigational product.

Early Termination From the Study

If a subject discontinued from the study for any reason prior to the final visit, the following procedures were conducted: adverse events and concomitant medications were recorded; an oral soft- and hard-tissue examination was performed; a follow-up visit was scheduled for any ongoing adverse events.

Results

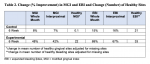

A total of six subjects who consented withdrew from the study. All subjects who completed the study demonstrated satisfactory compliance. Of those who started in the study, one adverse event occurred comprising an aphthous ulcer, which was determined to be unrelated to the study product and resolved without sequelae. Demographic data are provided in Table 1, and change (% improvement) in MGI and EBI and change (number) of healthy sites are given in Table 2.

The 6-week results of the MGI, EBI, and LSPI showed that the active treatment group (test mouthrinse) demonstrated highly statistically significant improvements during the study (P <.001).14 The active treatment was statistically superior to the control in biofilm reduction (P <.001), all LSPI endpoints (P <.001), and all MGI and EBI endpoints at both the 2-week and 6-week evaluations (with the exception of EBI healthy sites at 2 weeks).14 Also, BOP and PPD comparisons from baseline after 6 weeks of treatment resulted in a statistically significant decrease in BOP (P <.001) and PPD (P <.001) in the test group.14

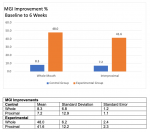

The 6-week MGI results demonstrated statistically significant gingival health improvements in the Test group only (Figure 1). The active mouthrinse treatment was about six times more effective in improving gingival health following 6 weeks of twice-daily use for both the whole mouth and interproximal areas compared to the Control group (brushing only) (P <.001).14

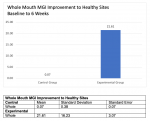

An evaluation of the change in the number of MGI healthy sites showed a similar pattern as seen for the overall MGI data. Specifically, there was a significant increase of 20 gingival healthy sites (based on color and swelling) for the active rinse group (adjusted for missing sites) (P <.001) compared to the Control group where less than one healthy site improved during the study.14 The superiority in change to healthy sites for the active treatment group was highly statistically significant (P <.001) compared to the Control group (Figure 2).14

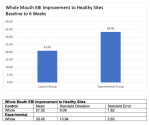

The mouthrinse treatment group also demonstrated positive improvements for EBI and was statistically superior to the Control group (P <.001) for the whole mouth and interproximal sites (Figure 3).14 The change in the number of gingival healthy (non-bleeding) sites increased nearly 50% for the EBI after adjustment for missing sites (P <.001).14 This was a statistically significant decrease of 30 bleeding sites for the active treatment group after 6 weeks of product use. In a direct comparison, the Control group resulted in an improvement of less than 20 healthy, non-bleeding sites during the 6-week study. The overall change toward a healthy gingival oral environment for the active mouthrinse treatment group was highly statistically significant (P <.001) at week 6 compared to the Control group (Figure 4).14

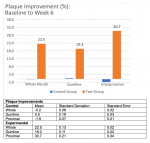

The mouthrinse treatment group achieved positive improvements for biofilm reduction and was again superior to the Control group (P <.001) for whole mouth, gumline, and interproximal sites (Figure 5).14 There were no statistically significant differences in plaque accumulations at each evaluation period during the 6-week study in the Control group.

Discussion

The active treatment provided positive outcomes toward gingival health improvements over the 6-week study for all clinical indicators of gingival inflammation assessed. Biofilm removal over the 6-week study in the active mouthrinse treatment group demonstrated an improvement over baseline that was not seen in the Control group. The active treatment rinse showed superiority for every endpoint evaluated in comparison to the Control group.

All endpoints for the active treatment group improved over the 6-week study (P <.001), and the improvements were highly superior to the Control group (P <.001).14 The change (% improvement) in MGI from diseased to the number of healthy sites at week 6 for the whole mouth and interproximal sites was about six times the improvement seen in the Control group.

All endpoints for the mouthrinse treatment group improved during the study and were significantly superior to the Control group (P <.001) except for EBI healthy sites at 2 weeks.14 Improvements were about four times greater for the active treatment group compared to the Control group at Week 6.

The change in the number of healthy sites for EBI improvements to healthy sites at week 6 for whole mouth interproximal sites was about 50% greater than the improvement seen in the Control group. These differences were statistically significant (P = .002 or better).14

Plaque did not statistically change from baseline for the Control group (brushing only) (P >.504).14 This was expected as the Control group was instructed to continue with their normal home brushing regimen. Conversely, the 6-week plaque accumulation for the active treatment group showed improvement throughout the study period, with whole mouth improvement of 22.5%.14

Plaque (whole mouth, interproximal, and gumline) for the active treatment group improved over the course of the study (P <.001), and the improvements were found to be superior to the Control group.14

The Control group regressed in BOP during the study, while the active treatment group had major gains in this category as evidenced by 66.7% less BOP for whole mouth in the Test group.14 All BOP assessments for the active treatment group demonstrated improvements that were statistically superior to the Control group.

The Test group had over 18 times improvement in PDD observed versus the Control group (the comparison was based on comparing whole mouth in both groups), while the PPD assessments for the active treatment demonstrated statistical superiority to the Control group.14 This finding is most likely a result of a significant decrease in the amount of gingival swelling (ie, pseudo-pocket) that was confirmed with the results from the MGI evaluation that assesses the swelling and color of the gingival unit.

OraCare Health Rinse contains chlorine dioxide, which has been shown to kill bacteria, viruses, and yeast, which are causative factors in gingival inflammation.15-17 With a reduction in oral bacteria levels through the use of a mouthrinse that can be easily used at home, thereby improving patient compliance, the immunological effects of bacteria that lead to gingival inflammation and the potential for accompanying bone loss can be mitigated (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Chlorine dioxide rinse (ie, OraCare Health Rinse) is an effective alternative to over-the-counter (eg, sodium fluoride-based, cetylpyridinium chloride-based) and prescription (eg, chlorhexidine-based) rinses that does not produce negative side effects commonly associated with these products. For example, chlorine dioxide does not contribute to tooth staining, burn oral tissues, or cause taste alteration. Also, chlorhexidine has been reported to affect fibroblasts, which may hamper healing. Coupled with the efficacy results, these characteristics help yield the added benefits of patient compliance and habit-forming potential.18,19

Conclusion

The active mouthrinse treatment investigated in this study was safe to use with no study-related adverse events reported. When the mouthrinse product was used twice daily for 6 weeks as an adjunct to toothbrushing, it provided adjunctive improvements in gingival health and plaque biofilm accumulation. Moreover, the oral care regimen to incorporate a simple mouthrinse procedure following toothbrushing resulted in a clinically proven gingival and biofilm improvement in just 2 weeks.

The oral rinse presented in this study and usedas an adjunct to toothbrushing with a fluoride toothpaste demonstrated an overall improvement in gingival health (604%) with a reduction in bleeding (455%) and significant reduction in probing depth (4,450%) when compared to brushing alone.14 Additionally, a plaque reduction of 225% was noted compared to the Control group, demonstrating the benefits of daily rinsing with this oral rinse. Patient compliance is key to maintenance of good oral homecare and plaque elimination with improved gingival health. Rinsing with the chlorine dioxide mouthwash is easy for patients to incorporate into their at-home oral care regimen and not time-consuming, helping to improve patient compliance. It aids patients in improving plaque removal and, therefore, their oral health without many of the issues commonly associated with over-the-counter and prescription mouthrinse products.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jeffery L. Milleman, DDS, MPA

Director, Clinical Operations and Principal Investigator, Salus Research, Inc., Fort Wayne, Indiana

Reinhard Schuller, MSc

Senior Consultant, Reinhard Schuller Consulting, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS, MAGD

Former Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Restorative Dentistry and Endodontics, University of Maryland School of Dentistry, Baltimore, Maryland; Diplomate, International Congress of Oral Implantologists; Private Practice, Silver Spring, Maryland

REFERENCES

1. Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, Van Dyke TE, et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89 suppl 1:S74-S84.

2. American Dental Association. Mouth Healthy™ A-Z Topics. Plaque. http://www.mouthhealthy.org/en/az-topics/p/plaque. Accessed August 15, 2024.

3. Ebel S, Blättermann H, Weik U, et al. High plaque levels after thorough toothbrushing: What impedes efficacy? JDR Clin Trans Res. 2019;4(2):135-142.

4. Nazir M, Al-Ansari A, Al-Khalifa K, et al. Global prevalence of periodontal disease and lack of its surveillance. ScientificWorldJournal. 2020;2020:2146160.

5. Bosma ML, McGuire JA, Sunkara A, et al. Efficacy of flossing and mouthrinsing regimens on plaque and gingivitis: a randomized clinical trial. J Dent Hyg. 2022;96(3):8-20.

6. Milleman J, Bosma ML, McGuire JA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of toothbrushing, flossing and mouthrinse regimens on plaque and gingivitis: a 12-week virtually supervised clinical trial. J Dent Hyg. 2022;96(3):21-34.

7. Milleman K, Milleman J, Bosma ML, et al. Role of manual dexterity on mechanical and chemotherapeutic oral hygiene regimens. J Dent Hyg. 2022;96(3):35-45.

8. Rotella K, Bosma ML, McGuire JA, et al. Habits, practices and beliefs regarding floss and mouthrinse among habitual and non-habitual users. J Dent Hyg. 2022;96(3):46-58.

9. Kurtzman GM, Horowitz RA, Johnson R, et al. The systemic oral health connection: biofilms. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(46):e30517.

10. Lobene RR, Weatherford T, Ross NM, et al. A modified gingival index for use in clinical trials. Clin Prev Dent. 1986;8(1):3-6.

11. Saxton CA, van der Ouderaa FJ. The effect of a dentifrice containing zinc citrate and triclosan on developing gingivitis. J Periodontol Res. 1989;24(1):75-80.

12. Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of victamine C. J Periodontol. 1970;41(1):41-43.

13. Lobene RR, Soparkar PM, Newman MB. Use of dental floss. Effect on plaque and gingivitis. Clin Prev Dent. 1982;4(1):5-8.

14. Clinical efficacy and safety evaluation of OraCare Health Rinse in adults on plaque and gingivitis in a six-week model (unpublished manuscript). November 27, 2023. https://www.oracareproducts.com/salusresearchstudy.html. Accessed August 15, 2024.

15. Herczegh A, Csák B, Dinya E, et al. Short- and long-term antibacterial effects of a single rinse with different mouthwashes: a randomized clinical trial. Heliyon. 2023;9(4):e15350.

16. Kerémi B, Márta K, Farkas K, et al. Effects of chlorine dioxide on oral hygiene - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(25):3015-3025.

17. Travis BJ, Elste J, Gao F, et al. Significance of chlorine-dioxide-based oral rinses in preventing SARS-CoV-2 cell entry. Oral Dis. 2022;28 suppl 2:2481-2491.

18. Rudolf JL, Moser C, Sculean A, Eick S. In-vitro antibiofilm activity of chlorhexidine digluconate on polylactide-based and collagen-based membranes. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):291.

19. Wyganowska-Swiatkowska M, Kotwicka M, Urbaniak P, et al. Clinical implications of the growth-suppressive effects of chlorhexidine at low and high concentrations on human gingival fibroblasts and changes in morphology. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37(6):1594-1600.