Understanding Periodontal-Endodontic Infections

Consistent terminology facilitates improved diagnosis and treatment

Yi-Chu Wu, DDS | Brooke Blicher, DMD | Rebekah Lucier Pryles, DMD | Jarshen Lin, DDS

Despite decades of literature describing periodontal-endodontic (perio-endo) lesions, they remain an often misunderstood disease entity. The anatomic connections between the dental pulp and the periodontium provide a pathway for perio-endo communication. Both of these tissues are mesenchymal in origin and once mature, remain connected via apical foramina, lateral canals, exposed dentinal tubules, and developmental grooves. These pathways provide an egress for pulpal disease to affect the periodontium and conversely, an ingress for periodontal disease to affect the pulp.1 Published literature on the subject exhibits variations in terminology, diagnostic criteria, and management strategies. These variations, as well as the clinical and radiographic similarities between perio-endo lesions and other dentoalveolar pathoses, complicate their diagnosis. To help clinicians better understand this unique and challenging pathologic entity, this article will review the history of perio-endo terminology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnoses, and multidisciplinary treatment strategies.

Coming to Terms

Definitions of perio-endo lesions exhibit significant variability in the literature. The initial classification system that was developed by Simon in 1972 is based on the presumed origin of the lesion, namely either the dental pulp or the periodontium.2 Diagnostic categories included primary endo, primary perio, primary endo/secondary perio, primary perio/secondary endo, and true combined lesions (Figure 1). In 1975, Guldener expanded upon Simon's classification system with regard to both the cause and the treatment of the lesion.3 He further divided primary endo/secondary perio lesions into those caused by acute or chronic periradicular pathoses or iatrogenic lesions following endodontic treatment, such as perforations. Primary perio/secondary endo lesions were further divided by pulp vitality, and combined lesions were left as a distinct category. Decades later, Torabinejad and Trope proposed yet another classification system, which was based on the origin of the periodontal pocket and used six categories: lesions of endodontic origin, lesions of periodontal origin, combined endo-perio lesions, separate endodontic and periodontal lesions, lesions with communication, and lesions without communication.4 In 2009, Abbott and Salgado proposed a simplified classification system that described perio-endo lesions as "concurrent" lesions, either with or without communication between the endodontic and periodontal pathoses.5 Despite the many changes proposed since 1972, Simon's original classification system remains the most universally accepted; therefore, the remainder of this article will utilize his original terminology.

Simon's Classification System

Simon classified perio-endo lesions based on both clinical and radiographic findings2:

Primary endo lesions originate from the dental pulp. Clinically, the pulp tissue is often completely necrotic. Periodontal attachment loss is not detectable. Swelling or sinus tracts, if present, are typically located in close proximity to the periapex. Radiographically, bony destruction is limited to the periapical area or the termini of the lateral canals. Marginal bone loss or intrabony defects are not expected.

Primary endo/secondary perio lesions develop from long-standing apical pathology. Expansion of the infection coronally along the periodontal ligament destroys adjacent bone until reaching the marginal periodontium. Clinically, pulp necrosis is expected, but unlike in a primary endo lesion, periodontal attachment loss is noted. Periodontal probing depths are often narrow. Swelling or sinus tracts may appear more coronally located than those associated with primary endo lesions without secondary perio involvement. Radiographically, bony destruction is often visible from the alveolar crest to the apical region (ie, apicomarginal defect).

Primary perio lesions originate from the marginal periodontium. Clinical findings include periodontal attachment loss and mobility. Unlike the narrow defects observed in primary endo lesions, in primary perio lesions, the periodontal pocket is often wide. The dental pulp, however, is vital. Radiographically, horizontal bone loss and intrabony defects starting from the marginal bone are often observed. Apical pathology is undetectable in these cases.

Primary perio/secondary endo lesions result from extension of the periodontal pocket along the root structure to the apical foramina or lateral canals. Clinical findings are similar to those observed in primary perio lesions; however, pulp vitality is compromised. Radiographically, extension of the intrabony defect is visible to the apical foramina.

True combined lesions result from the coalescence of independent periodontal and endodontic lesions. Clinical and radiographic findings are often similar to those noted for primary perio/secondary endo lesions. Clinically, wide periodontal pockets and a nonvital pulp are present, and radiographically, an apicomarginal bony defect is visible.

The endodontic and periodontal findings associated with perio-endo lesions are similar to several other pathologic entities that must be included in the differential diagnosis. Other pathologic entities that present similarly to perio-endo lesions include vertical root fractures, periodontal bone loss resulting from complications during endodontic treatment, anatomic defects such as deep grooves, and in rare cases, intra-alveolar malignancies and metastatic diseases.6 Careful assessment of patient history and meticulous clinical and radiographic exams are required to accurately differentiate between perio-endo lesions and other disease entities. In some cases, surgical exposure or biopsy may also be necessary to establish a proper diagnosis.

Treatment

Proper diagnosis facilitates appropriate treatment, and perio-endo lesions may be readily treated. Management strategies for each of Simon's diagnostic categories are presented below.7

The treatment for primary endo lesions involves nonsurgical root canal therapy and appropriate restorative care. In these cases, periodontal intervention is not necessary, and outcomes for these teeth are quite predictable. Success rates for nonsurgical root canal therapy are reported in the literature to be as high as 97%.8

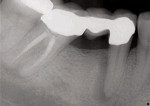

Primary endo/secondary perio cases require multidisciplinary management, including endodontic intervention and, potentially, basic periodontal therapy. In these cases, the periodontal pocket forms via destruction of the attachment apparatus by chronic inflammatory mediators stimulated by the local infection. Although endodontic intervention removes the bacterial stimulus for attachment loss, the overall prognosis depends on the remaining periodontal attachment and the morphology of the radicular bone and supporting periodontal tissue. Dramatic healing can occur with proper management,7 and some primary endo/secondary perio lesions respond well to endodontic therapy alone. (Figure 2 through Figure 4).

Primary perio/secondary endo lesions and true combined lesions also require multidisciplinary management; however, given the degree of attachment loss present, periodontal regenerative procedures are often necessary as well. If the endodontic infection is controlled, the prognosis of the tooth is ultimately determined by the treatability of the periodontal defect, which is based on the extent of the attachment loss and the morphology of the defect.7 Clinical attachment loss has a demonstrably negative impact on the prognosis of endodontically treated teeth.9 For both of these diagnostic categories, root canal therapy should be performed prior to periodontal intervention. Although marginal bone levels will be unaffected by endodontic intervention, control of the pulpal infection is imperative to the success of periodontal therapies.10 Upon completion of endodontic treatment, initial periodontal therapy should include scaling and root planing or flap debridement to decrease the microbiologic burden in the periodontal pocket. After a 3-to-6 month period following the completion of endodontic treatment, apical healing should be evaluated and the periodontal condition reassessed. At this time, if adequate healing has occurred, periodontal regenerative therapies can be utilized. These include tissue engineering techniques, such as guided tissue regeneration (GTR); implantation of enamel protein matrix derivatives; and application of signaling molecules, such as growth factors.11 These therapies promote the formation of new cementum, periodontal ligament, and bone to achieve esthetic and hygienic goals.12 For cases with severe periodontal defects not amenable to regenerative therapies, root resection may also be considered.13 The treatment of cases of primary perio/secondary endo and true combined lesions is significantly less predictable than that of those arising due to primary endo disease.14 Without concomitant regenerative procedures, success ranges from 27% to 37%.15 When regenerative procedures are added to endodontic therapy, the chance of a successful outcome improves to 77.5%.11 Failure to address these lesions can result in progressive bone loss and eventual loss of affected teeth (Figure 5 through Figure 7). Recommended treatment strategies are reviewed in Figure 8.

Conclusion

Perio-endo pathoses present a diagnostic challenge for many practitioners. This is often compounded by the varied terminology utilized in the literature. As with other interdisciplinary topics, using consistent terminology to facilitate a comprehensive and systematic approach to diagnosis and treatment will result in more effective treatment and improved outcomes for patients.

References

1. Schmidt JC, Walter C, Amato M, et al. Treatment of periodontal-endodontic lesions--a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(8):779-790.

2. Simon JH, Glick DH, Frank AL. The relationship of endodontic-periodontic lesions. J Periodontol. 1972;

43(4):202-208.

3. Guldener PHA. The relationship between pulp and periodontal diseases. Deutsche Zahnärtzliche Zeitschft. 1975;30(6);377-379.

4. Torabinejad M, Trope M. Endodontic and periodontal interrelationships. In: Walton RE and Torabinejad M, eds. Principles and Practice of Endodontics,. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elseveir;1996.

5. Abbott PV, Salgado JC. Strategies for the endodontic management of concurrent endodontic and periodontal diseases. Aust Dent J. 2009;54(Suppl l):

S70-S85.

6. Levi PA Jr, Kim DM, Harsfield SL, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma presenting as an endodontic-periodontic lesion. J Periodontol. 2005;76(10):1798-1804.

7. Rotstein I, Simon JH. Diagnosis, prognosis and decision-making in the treatment of combined periodontal-endodontic lesions. Periodontol 2000. 2004;34:

165-203.

8. Salehrabi R, Rotstein I. Endodontic treatment outcomes in a large patient population in the USA: an epidemiological study. J Endod. 2004;30(12):846-850.

9. Setzer FC, Boyer KR, Jeppson JR, et al. Long-term prognosis of endodontically treated teeth: a retrospective analysis of preoperative factors in molars. J Endod. 2011;37(1):21-25.

10. Nyman S, Lindhe J. A longitudinal study of combined periodontal and prosthetic treatment of patients with advanced periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1979;50(4):163-169.

11. Kim E, Song Js, Jung IY, Lee SJ, Kim S. Prospective clinical study evaluating endodontic microsurgery outcomes for cases with lesions of endodontic origin compared with cases with lesions of combined periodontal-endodontic origin. J Endod. 2008;34(5):

546-551.

12. Bashutski JD, Wang HL. Periodontal and Endodontic Regeneration. J Endod. 2009;35(3):321-328

13. Blömlof L, Jansson L, Appelgren R, et al. Prognosis and mortality of root-resected molars. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1997;17(2):190-201.

14. McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual outcome. II. The effectiveness of clinical parameters in developing an accurate prognosis. J Periodontol. 1996;

67(7):658-665.

15. Oh SL, Fouad AF, Park SH. Treatment strategy for guided tissue regeneration in combined endodontic-periodontal lesions: case report and review. J Endod. 2009;35(10):1331-1336.

About the Authors

Yi-Chu Wu, DDS

Staff Dentist

Taipei Chang Gung Memorial Hospital

Taipei, Taiwan

Team Dentist

Greencross Medical Service Team

Taipei Medical University

Yunlin, Taiwan

Brooke Blicher, DMD

Upper Valley Endodontics, PC

White River Junction, Vermont

Assistant Clinical Professor

Department of Endodontics

Tufts University School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Clinical Instructor

Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterials Science

Harvard School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Rebekah Lucier Pryles, DMD

Upper Valley Endodontics, PC

White River Junction, Vermont

Assistant Clinical Professor

Department of Endodontics

Tufts University School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Jarshen Lin, DDS

Director of Predoctoral Endodontics

Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterials Science

Harvard School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Clinical Associate

Department of Oral and

Maxillofacial Surgery

Massachusetts General Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts